WE ARE READY TO BRING YOU TOGETHER WITH ART %60 Discount

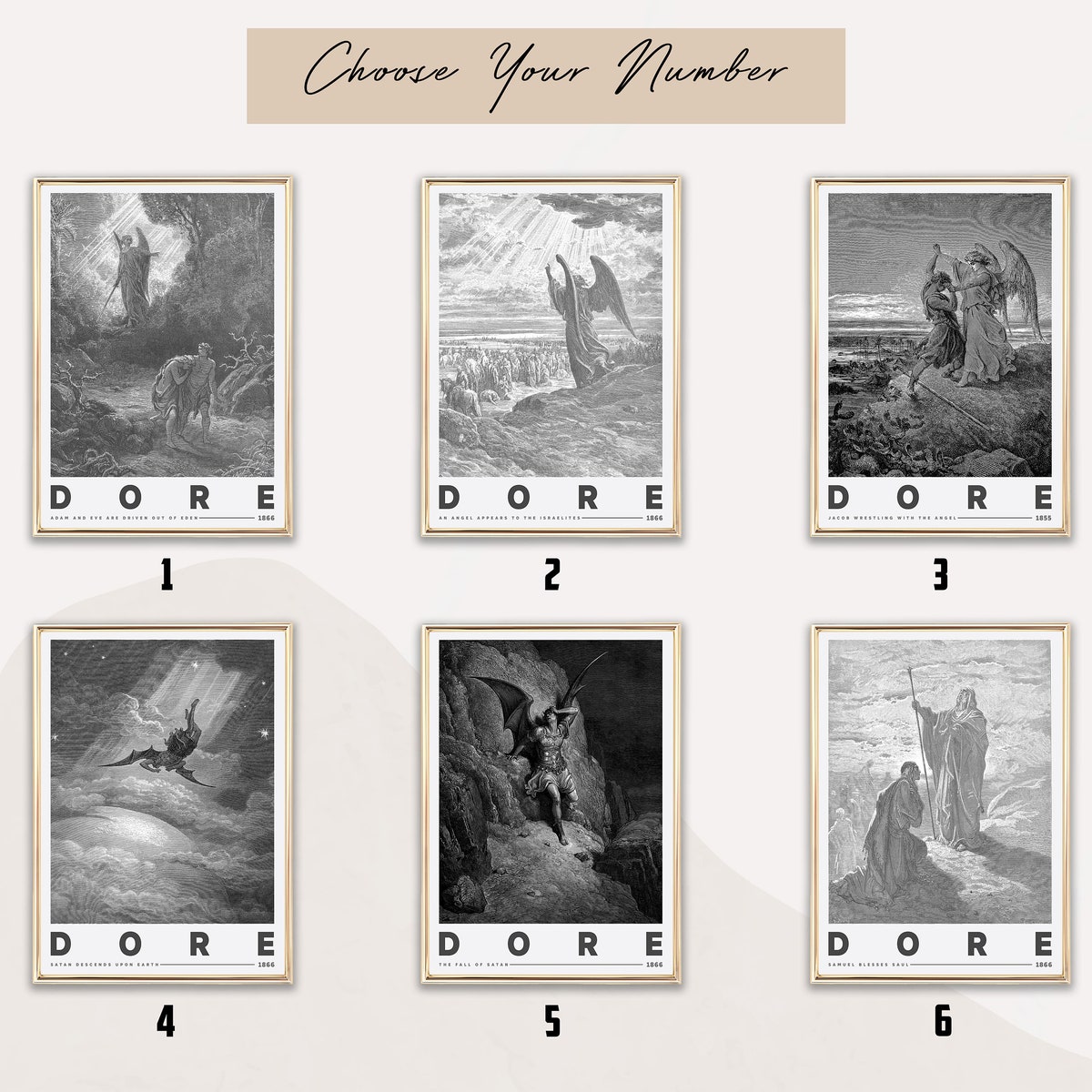

Gustave Doré’s Epic Worlds of Light and Shadow

A Visionary of 19th-Century Fantasy

Born in Strasbourg in 1832, Gustave Doré displayed an uncanny facility with multiple artistic disciplines from the very outset of his career. Long before physical exhibitions or gallery labels, he produced weekly lithographs for various journals and albums, revealing a work ethic that would define his entire life. He exhibited a versatile skill set, handling painting, sculpture, engraving, and illustration with equal aplomb. His early drive to immerse himself in different techniques foreshadowed a vast and multifaceted body of work that continues to captivate audiences. His early experiments in print and sculpture already hinted at a restless creative spirit.

Over the decades that followed, Doré cultivated a reputation as a narrative artist par excellence. By translating the words of literary luminaries into theatrical visual experiences, he transformed abstract text into ripple-charged scenes. His imagination drew upon Romantic and symbolic traditions, yet it also bore the mark of a sharp social observer. Whether depicting the dusty streets of an old city or the spark in a peasant’s eye, he infused each work with both grandeur and human immediacy.

Central to Doré’s practice was a collaborative studio model that propelled his creative output onto an industrial scale. He orchestrated teams of woodcutters who translated his drawings into reproducible wood engravings, a process that enabled a wide readership to encounter his imagery. This approach positioned Doré as more than an illustrator; he became a printmaker who democratized access to richly illustrated literature during a period of rising literacy. His dedication to collaborative craft amplified the reach and resonance of every project he undertook. Those collaborations underscored his belief in art as a collective endeavor.

By the end of his career, Doré had illustrated more than ninety books, ranging from classic novels to sacred texts. His name became synonymous with epic visual storytelling, and his engravings carved a place for illustrated narrative in the Victorian imagination. Today, his Strasbourg beginnings and his tireless studio practice remind us that his achievements rested equally on personal talent and on his capacity to harness the energies of many hands.

Crafting Narrative Through Light and Composition

At the heart of Doré’s work lies a mastery of dramatic space, where sweeping panoramas collide with moments of intimate tension. His wood-engraved illustrations often employ monumental architecture as a stage for human drama, from soaring cathedral vaults to the fiery chasms of hellish caverns. In each scene, he choreographs cascades of figures, guiding the viewer’s eye through a carefully constructed interplay of scale and gesture. This cinematic sensibility underscores his scenes with a palpable sense of movement and suspense.

Doré’s visual vocabulary balances Romantic grandeur with grotesque and sublime details that speak to the era’s fascination with moral and existential themes. He could depict an entire army of lost souls writhing in Dante’s inferno one instant, and then focus on the solitary anguish of a single figure the next. His skill with chiaroscuro—juxtaposing deep shadows against bright highlights—heightens every emotional note, whether it be terror, awe, or quiet contemplation. Such contrasts anchor each image to a specific narrative moment, yet allow it to resonate with universal human concerns. Doré understood how visual extremes could mirror the complexities of human morality.

The material reality of wood engraving itself shaped Doré’s aesthetic decisions, compelling him to think in terms of texture and line that could endure mass reproduction. His precise draftsmanship translated effectively into the hands of experienced woodcutters, ensuring that the nuances of his shading and the drama of his compositions survived the transition from drawing to print. By embracing the technical demands of this medium, Doré forged images that combined fidelity to literary texts with the raw energy of a theatrical set design.

Through this alchemy of light, shadow, and meticulous detail, Doré’s illustrations became interpretive anchors for readers encountering complex stories. His rendering of Balzac’s social landscapes or Cervantes’ fantastical wanderings does more than capture narrative events; it extends an invitation to explore the ethical and emotional undercurrents of those tales. In so doing, Doré elevated illustration beyond mere accompaniment and into the realm of active storytelling.

Enduring Echoes in Visual Storytelling

More than a century after his passing, Gustave Doré’s images continue to shape how we visualize the sublime and the grotesque. His synthesis of Romantic drama and symbolic nuance laid the groundwork for early Symbolist painters and foreshadowed modern graphic narrative techniques. Generations of artists, from editorial illustrators to concept designers, have drawn on his dense compositions and charged atmospheres as a template for constructing immersive visual worlds. His work stands at a crossroads between moral instruction and imaginative exploration.

By democratizing access to illustrated classics, Doré created a shared visual language that transcended national and linguistic boundaries. His Bible and Dante illustrations, widely circulated in popular editions, invited readers across Europe to engage with sacred and literary texts in a richly textured way. This broad dissemination helped cement his status as a cultural touchstone, one whose images could convey complex emotional and ethical ideas to a diverse audience eager for epic narratives. His prints crossed social divides and sparked conversations that extended beyond any single edition.

Today, curators and scholars frequently reference Doré’s achievements when tracing the evolution of book illustration in the nineteenth century. Museum exhibitions devoted to his engravings reintroduce contemporary viewers to a moment when illustrated narratives were central to public imagination. His studio’s capacity to translate prose into unforgettable visuals remains a reference point for any discussion of the illustrator’s power to steer reader response and enhance textual meaning.

Ultimately, the legacy of Gustave Doré endures in every image that seeks to fuse moral gravity with spectacular imagery. His work reminds us that illustration is not a subservient craft but a dynamic form of interpretation, one that can infuse a text with new layers of meaning through the orchestration of light, shadow, and form. At a time when visual storytelling spans digital and print domains alike, Doré’s achievements stand as a testament to the enduring power of illustrated narrative.